Hematological Disorder & Blood Test

Hematological disorders, also known as blood disorders, affect the blood and blood-forming organs, impacting the quantity and function of blood cells and proteins. Common hematological disorders are anemia, bleeding disorders (like hemophilia), blood clots, and blood cancers such as leukemia, lymphoma, and myeloma. Symptoms vary but can include fatigue, weakness, frequent infections, unexplained bruising or bleeding, shortness of breath, and swelling in limbs.

Common Hematological Disorders and their Clinical Features:

- Anemia: Characterized by a deficiency in red blood cells or hemoglobin, leading to reduced oxygen-carrying capacity. Clinical features include fatigue, weakness, pale skin, shortness of breath, and dizziness.

- Bleeding Disorders (e.g., Hemophilia, Von Willebrand Disease):These disorders affect the blood’s ability to clot, causing excessive or prolonged bleeding. Clinical features include easy bruising, bleeding gums, prolonged bleeding from minor cuts, nosebleeds, heavy menstrual bleeding, and joint bleeding.

- Blood Clotting Disorders (e.g., Thrombophilia):These disorders can cause abnormal blood clots to form in blood vessels. Clinical features include swelling, pain, redness, and warmth in the affected area.

- Blood Cancers (e.g., Leukemia, Lymphoma, Myeloma):These cancers affect the blood-forming cells in the bone marrow. Clinical features include fatigue, frequent infections, unexplained fever, night sweats, weight loss, bone pain, and swollen lymph nodes.

- Thrombocytopenia: A condition where there is a low platelet count, which can lead to bleeding and bruising. Clinical features include easy bruising, prolonged bleeding from cuts, and pinpoint red spots on the skin.

- Sickle Cell Disease: A genetic disorder where red blood cells become rigid and crescent-shaped, causing pain crises, anemia, and other complications.

- Thalassemia: An inherited blood disorder where the body makes abnormal hemoglobin, leading to anemia and other complications.

General Symptoms of Blood Disorders:

Beyond the specific features of each disorder, some general symptoms may indicate a hematological issue:

- Fatigue and Weakness: A common symptom due to reduced oxygen delivery to the body.

- Frequent Infections: May indicate a problem with white blood cells, which fight off infections.

- Unexplained Bruising or Bleeding: A sign of platelet or clotting factor problems.

- Shortness of Breath: Can be caused by anemia or other conditions affecting oxygen transport.

- Swelling in Limbs: May indicate blood clotting disorders.

- Pale or Yellowed Skin: Common in anemia and certain liver-related blood disorders.

- Pain in Bones or Joints: Seen in conditions like sickle cell disease.

- Fever and Night Sweats: May be associated with blood cancers.

Classification of Anemia

Anemia can be classified based on red blood cell morphology (size and hemoglobin content) or the underlying cause or pathophysiology. Morphologically, anemias are classified as microcytic, normocytic, or macrocytic, depending on the size of the red blood cells. They can also be classified as normochromic, hypochromic, or hyperchromic based on hemoglobin content. Pathophysiologically, anemias can be classified by increased red blood cell loss or destruction, or decreased red blood cell production.

Morphological Classification:

- Microcytic Anemia: Red blood cells are smaller than normal (low MCV) and can be associated with iron deficiency, thalassemia, or anemia of chronic disease.

- Normocytic Anemia: Red blood cells are of normal size and hemoglobin content (normal MCV, MCH, and MCHC). This can be seen in acute blood loss, chronic disease, or kidney disease.

- Macrocytic Anemia: Red blood cells are larger than normal (high MCV). Causes include vitamin B12 or folate deficiency, liver disease, or certain medications.

- Normochromic: Red blood cells have a normal amount of hemoglobin.

- Hypochromic: Red blood cells have a decreased amount of hemoglobin.

- Hyperchromic: Red blood cells have an increased amount of hemoglobin.

Pathophysiological Classification:

- Increased Red Blood Cell Loss or Destruction:This can be due to acute hemorrhage (bleeding), hemolytic anemia (where red blood cells are destroyed prematurely), or autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

- Decreased Red Blood Cell Production:This can be due to bone marrow failure (aplastic anemia), deficiencies in iron, vitamin B12, or folate, or anemia associated with chronic diseases like kidney disease.

Other ways to classify anemia:

- Severity:Anemia can be classified as mild, moderate, or severe based on hemoglobin levels.

- Cause:Anemias can also be classified by their underlying cause, such as iron deficiency anemia, vitamin deficiency anemia, or anemia of chronic disease.

Microcytic Anemia

Microcytic anemia is a condition where red blood cells are abnormally small, often due to insufficient iron or defects in hemoglobin production. Causes include iron deficiency, chronic diseases, thalassemia, and lead poisoning. Symptoms can range from fatigue and pale skin to more severe issues like heart problems. Diagnosis involves blood tests, specifically a complete blood count (CBC) and iron studies. Treatment focuses on addressing the underlying cause, often with iron supplements or managing chronic conditions.

Causes of Microcytic Anemia:

- Iron Deficiency: The most common cause, due to inadequate iron intake, poor absorption, or blood loss (e.g., from menstruation, gastrointestinal bleeding).

- Thalassemia: Genetic disorders affecting globin chain production, leading to abnormal hemoglobin and small red blood cells.

- Anemia of Chronic Disease: Inflammatory conditions can interfere with iron utilization and red blood cell production.

- Sideroblastic Anemia: Rare disorders where the body can’t incorporate iron into hemoglobin.

- Lead Poisoning: Lead can interfere with heme synthesis, leading to microcytic anemia.

Clinical Features (Symptoms):

- Fatigue and weakness

- Pale skin, mucous membranes, or nail beds

- Shortness of breath

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Fast heartbeat

- Irritability

- Pica (craving non-food items like ice, dirt)

- Cold hands and feet

- Headaches

- In severe cases, chest pain or confusion

Diagnosis:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Shows smaller-than-normal red blood cells (microcytosis) and reduced hemoglobin levels.

- Peripheral Blood Smear: Visual assessment of red blood cell size and shape.

- Iron Studies: Measure serum iron, ferritin, total iron-binding capacity (TIBC), and transferrin saturation to assess iron stores and transport.

- Hemoglobin Electrophoresis: May be used to diagnose thalassemia.

- Other tests: Depending on the suspected cause, tests for lead levels, stool for occult blood, or bone marrow biopsy may be needed.

Pathological Tests (in addition to those listed above):

- Reticulocyte Count: Measures the number of immature red blood cells. A low count suggests decreased red blood cell production.

- Serum Iron and Ferritin: Help to evaluate iron stores.

- Total Iron-Binding Capacity (TIBC): Measures the blood’s capacity to bind iron. High TIBC can indicate iron deficiency.

Treatment:

- Iron Deficiency Anemia: Oral or intravenous iron supplementation, dietary changes (increasing iron-rich foods and vitamin C), and addressing underlying causes of blood loss.

- Thalassemia: May involve blood transfusions, iron chelation therapy, or bone marrow transplantation.

- Anemia of Chronic Disease: Managing the underlying inflammatory condition.

- Sideroblastic Anemia: May involve pyridoxine (vitamin B6) supplementation, or other treatments depending on the specific type.

- Lead Poisoning: Chelation therapy to remove lead from the body.

Complications:

- Heart Problems:In severe cases, especially in children, untreated microcytic anemia can lead to heart enlargement or failure.

- Developmental Delays:Children with severe, untreated anemia may experience developmental delays.

- Fatigue and Reduced Quality of Life:Even mild anemia can significantly impact energy levels and daily activities.

Prevention:

- Iron-rich diet: Include foods like red meat, beans, spinach, and fortified cereals.

Normocytic Anemia

Normocytic anemia is characterized by red blood cells (RBCs) that are normal in size and hemoglobin content but are reduced in number. This can result from impaired production of RBCs, increased destruction or loss of RBCs, or dilution of RBCs due to increased plasma volume. Common causes include chronic diseases, acute blood loss, bone marrow disorders, and certain infections. Symptoms can include fatigue, weakness, pale skin, shortness of breath, and dizziness. Diagnosis involves a complete blood count (CBC), reticulocyte count, and potentially a bone marrow biopsy. Treatment depends on the underlying cause and may involve addressing the primary condition, medications, blood transfusions, or dietary changes.

Causes:

- Chronic Diseases: Anemia of chronic disease, often associated with conditions like kidney disease, cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and chronic infections, is a common cause.

- Acute Blood Loss: Significant blood loss from trauma, surgery, or gastrointestinal bleeding can lead to normocytic anemia.

- Bone Marrow Disorders: Conditions like aplastic anemia, where the bone marrow doesn’t produce enough blood cells, can result in normocytic anemia.

- Hemolytic Anemia: This type of anemia occurs when red blood cells are destroyed faster than the body can replace them.

- Endocrine Disorders: Conditions like hypothyroidism can contribute to normocytic anemia.

- Medications: Some medications can cause or worsen anemia.

Clinical Features:

- Fatigue and Weakness: A general feeling of tiredness and lack of energy is a common symptom.

- Pale Skin: Reduced red blood cells can lead to a pale complexion, especially noticeable in the skin and mucous membranes.

- Shortness of Breath: Reduced oxygen-carrying capacity can cause shortness of breath, especially during physical activity.

- Dizziness and Lightheadedness: Insufficient oxygen to the brain can cause these symptoms.

- Rapid Heartbeat: The heart may beat faster to compensate for the reduced oxygen delivery.

- Other Symptoms: Chest pain, headaches, and difficulty concentrating can also occur.

Diagnosis:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC):This test measures the number and characteristics of blood cells, including red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

- Reticulocyte Count:This test measures the number of immature red blood cells, which can help determine if the bone marrow is producing enough new red blood cells.

- Iron Studies:These tests assess iron levels in the blood, which can be helpful in determining the cause of anemia.

- Bone Marrow Biopsy:In some cases, a bone marrow biopsy may be necessary to assess the bone marrow’s ability to produce blood cells.

- Other Tests:Depending on the suspected cause, additional tests like kidney function tests, liver function tests, or autoimmune antibody tests may be performed.

Pathological Tests:

- Peripheral Blood Smear:Examining a blood smear under a microscope can help identify the size, shape, and appearance of red blood cells, helping to differentiate between normocytic and other types of anemia.

- Bone Marrow Examination:In cases where the cause of anemia is unclear, a bone marrow biopsy may be performed to evaluate the bone marrow’s cellularity and identify any abnormalities.

Macrocytic Anemia

Macrocytic anemia is a condition where red blood cells are larger than normal, often due to deficiencies in vitamin B12 or folate, or other underlying conditions. Clinical features include fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath, but symptoms can vary based on the underlying cause. Diagnosis involves blood tests, including a complete blood count (CBC) and vitamin level tests. Treatment focuses on addressing the root cause, which may involve vitamin supplementation, dietary changes, or treatment of other medical conditions.

Causes:

- Megaloblastic:

- Vitamin B12 deficiency: Pernicious anemia (autoimmune destruction of stomach cells), inadequate dietary intake, malabsorption (e.g., Crohn’s disease, ileal resection).

- Folate deficiency: Poor diet, increased demand (pregnancy), malabsorption, medications (e.g., methotrexate).

- Non-megaloblastic:

- Liver disease: Alcoholism, chronic liver disease.

- Hypothyroidism: Underactive thyroid gland.

- Myelodysplastic syndromes: Bone marrow disorders.

- Certain medications: Some chemotherapy drugs, anticonvulsants.

- Increased reticulocyte production: Hemolytic anemia, blood loss.

Clinical Features:

- General anemia symptoms: Fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath, pale skin.

- Neurological symptoms (megaloblastic): Numbness, tingling, balance problems, memory loss (especially with B12 deficiency).

- Gastrointestinal symptoms: Diarrhea, smooth and sore tongue (glossitis).

- Cardiovascular symptoms: Rapid heartbeat, heart failure (in severe cases).

Diagnosis:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Measures red blood cell size (MCV), hemoglobin, and other parameters.

- Peripheral Blood Smear: Examines red blood cell morphology (size, shape, and appearance).

- Vitamin B12 and Folate levels: Assesses for deficiencies.

- Bone marrow biopsy: May be needed in some cases to assess red blood cell production.

- Other tests: Liver function tests, thyroid function tests, etc., to identify underlying causes.

Pathological Tests:

- Megaloblastic: Hypersegmented neutrophils (more than 5 lobes) in the blood smear.

- Non-megaloblastic: May show abnormal red blood cell shapes and other abnormalities related to the underlying condition.

Treatment:

- Megaloblastic:

- Vitamin B12 supplementation: Injections or oral supplements.

- Folate supplementation: Oral supplements.

- Non-megaloblastic:

- Treat the underlying condition: Address liver disease, hypothyroidism, etc.

- Discontinue or reduce offending medications: As appropriate.

Complications:

- Untreated megaloblastic anemia: Neurological damage (e.g., nerve damage, dementia), heart failure.

- Untreated non-megaloblastic anemia: Complications related to the underlying condition (e.g., liver failure, heart problems).

Prevention:

- Balanced diet: Includes sufficient vitamin B12 and folate (especially important for vegetarians and vegans).

- Early diagnosis and treatment of underlying conditions: Regular health checkups can help identify issues early.

- Avoid excessive alcohol consumption: Can lead to liver damage and anemia.

- Be aware of medication side effects: Discuss potential anemia risks with your doctor.

Normochromic Anemia

Normochromic anemia refers to a type of anemia where red blood cells have a normal color (normal amount of hemoglobin) but are present in insufficient quantities. This condition is often a consequence of an underlying disease or chronic illness, rather than a primary disorder of red blood cell production itself.

Causes:

- Chronic Diseases:Conditions like kidney disease, autoimmune disorders (lupus, rheumatoid arthritis), chronic infections, and certain cancers can lead to normochromic anemia.

- Bone Marrow Failure:Aplastic anemia, where the bone marrow doesn’t produce enough blood cells, can also result in normochromic anemia.

- Blood Loss:Chronic blood loss, even if not immediately apparent, can deplete the body’s red blood cell stores.

- Hemolysis:Excessive destruction of red blood cells, either due to inherited conditions or acquired factors, can lead to normochromic anemia.

- Endocrine Disorders:Conditions like hypothyroidism can also contribute.

- Early Iron Deficiency:In some cases, normochromic anemia can be an early stage of iron deficiency before it progresses to microcytic anemia.

Clinical Features:

- Symptoms are often related to reduced oxygen delivery to tissues and organs, and can include:

- Fatigue and weakness

- Shortness of breath

- Dizziness and lightheadedness

- Pale skin and mucous membranes

- Headaches

- Chest pain

- Rapid heartbeat

- Reduced endurance

Diagnosis:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC):This test measures red blood cell count, hemoglobin levels, and other parameters, including Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV) and Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration (MCHC).

- Reticulocyte Count:Measures the number of immature red blood cells, indicating the bone marrow’s response to anemia.

- Iron Studies:Assess iron levels and iron-binding capacity to rule out iron deficiency as a cause.

- Bone Marrow Biopsy:In some cases, a bone marrow biopsy may be needed to evaluate the bone marrow’s cellularity and identify the cause of anemia.

- Other Tests:Depending on the suspected cause, tests for kidney function, autoimmune markers, thyroid function, or specific infections may be performed.

Pathological Tests:

- Peripheral Blood Smear:Examination of blood cells under a microscope can reveal characteristics like size, shape, and presence of inclusions, which can provide clues about the cause of anemia.

- Bone Marrow Aspiration and Biopsy:These tests allow for detailed examination of bone marrow cells and can reveal abnormalities in red blood cell production or the presence of other diseases.

Treatment:

- Treating the Underlying Cause:The primary focus is on addressing the root cause of the anemia. This may involve treating infections, managing chronic diseases, or addressing endocrine disorders.

- Blood Transfusions:In severe cases, blood transfusions may be necessary to quickly raise red blood cell levels.

- Erythropoietin (EPO) Therapy:EPO is a hormone that stimulates red blood cell production. It may be used in cases of anemia related to kidney disease or other conditions.

- Iron Supplements:If iron deficiency is present (even if not the primary cause), iron supplements may be needed.

- Dietary Changes:A balanced diet rich in iron, folate, and vitamin B12 is important for overall red blood cell health and can help prevent or manage anemia.

Complications:

- Heart Failure: Severe anemia can put extra strain on the heart, leading to heart failure.

- Neurological Problems: In some cases, anemia can affect the nervous system, leading to neurological symptoms.

- Growth and Development Issues: In children, anemia can affect growth and development.

- Increased Risk of Infections: Reduced red blood cells can impair the immune system, making individuals more susceptible to infections.

Hypochromic Anemia

Hypochromic anemia is a condition where red blood cells are pale and smaller than normal due to insufficient hemoglobin. This is often caused by iron deficiency, but can also stem from other conditions like thalassemia or anemia of chronic disease. Symptoms can include fatigue, shortness of breath, and pale skin. Diagnosis involves blood tests, including a complete blood count (CBC) and iron studies. Treatment focuses on addressing the underlying cause, often through iron supplementation or managing chronic diseases.

Causes:

- Iron Deficiency: The most common cause, due to inadequate dietary intake, poor absorption, or blood loss.

- Thalassemia: Genetic disorders affecting hemoglobin production.

- Anemia of Chronic Disease: Inflammation or chronic illnesses can interfere with iron utilization.

- Other Causes: Sideroblastic anemia, lead poisoning, and certain drug-induced anemias can also lead to hypochromic anemia.

Clinical Features:

- Fatigue and Weakness: Reduced oxygen delivery to tissues leads to tiredness and lack of energy.

- Shortness of Breath: Difficulty breathing, especially during exertion, due to reduced oxygen-carrying capacity.

- Pale Skin: Reduced hemoglobin levels cause a lighter skin tone.

- Other Symptoms: Dizziness, headache, brittle nails, mouth ulcers, and pica (craving non-food items) can also occur.

Diagnosis:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC):Measures red blood cell count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and indices like MCV (mean corpuscular volume) and MCHC (mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration).

- Peripheral Blood Smear:Microscopic examination of blood cells to assess size and shape (microcytosis and hypochromia).

- Iron Studies:Measure serum iron, ferritin, TIBC (total iron-binding capacity), and transferrin saturation to evaluate iron status.

- Other Tests:May include bone marrow examination, hemoglobin electrophoresis, and tests for specific underlying conditions.

Pathological Tests:

- Microscopic Examination of Blood Smear: Reveals smaller and paler red blood cells than normal.

- Low Hemoglobin and Hematocrit: Indicates reduced oxygen-carrying capacity.

- Low MCV and MCHC: Reflects the smaller size and reduced hemoglobin content of red blood cells.

Treatment:

- Iron Supplementation: Oral or intravenous iron supplements for iron deficiency.

- Treating Underlying Conditions: Managing chronic diseases, addressing infections, or other specific causes.

- Blood Transfusion: In severe cases, to rapidly increase red blood cell levels.

- Nutritional Support: Ensuring adequate intake of iron, folate, and vitamin B12 through diet or supplements.

Complications:

- Severe Anemia: Can lead to organ damage and failure if untreated.

- Iron Overload: Can occur with certain genetic conditions or excessive iron supplementation, leading to liver damage and other complications.

- Increased Infection Risk: Compromised immune function due to anemia.

- Growth and Development Issues: Can affect children and adolescents.

Prevention:

- Adequate Iron Intake: Consuming iron-rich foods or taking supplements as needed.

- Managing Underlying Conditions: Early diagnosis and treatment of conditions that can cause anemia.

- Prenatal Care: Ensuring adequate iron and folate intake during pregnancy.

- Promoting Healthy Lifestyle: A balanced diet and regular exercise can help prevent anemia.

Hyperchromic Anemia

Hyperchromic anemia, characterized by abnormally high concentration of hemoglobin in red blood cells, is typically associated with vitamin B12 or folate deficiency, rather than iron deficiency, which causes hypochromic anemia. The condition can also arise from problems with DNA synthesis, affecting red blood cell maturation. Symptoms can include fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath, and neurological issues. Diagnosis involves blood tests like complete blood count (CBC) and possibly a bone marrow biopsy. Treatment focuses on addressing the underlying deficiency through dietary changes or supplementation.

Causes:

- Vitamin B12 Deficiency:Often due to pernicious anemia (inability to absorb B12), dietary deficiencies, or conditions affecting the small intestine.

- Folate Deficiency:Can result from poor diet, malabsorption issues, or increased folate needs during pregnancy.

- DNA Synthesis Problems:Disruptions in DNA synthesis can affect red blood cell maturation, leading to macrocytic (large) and hyperchromic (high hemoglobin concentration) cells.

- Rare Genetic Conditions:Some inherited disorders can also cause hyperchromic anemia.

Clinical Features:

- Fatigue and Weakness: Common symptoms due to reduced oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood.

- Shortness of Breath: Especially with exertion.

- Neurological Symptoms: Vitamin B12 deficiency can cause nerve damage, leading to tingling, numbness, and gait problems.

- Pale Skin and Mucous Membranes: A classic sign of anemia, but may be subtle.

- Other symptoms: May include dizziness, headache, chest pain, and in severe cases, heart problems.

Diagnosis:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC):Measures red blood cell count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, and mean corpuscular volume (MCV). In hyperchromic anemia, MCV is elevated, indicating larger than normal red blood cells.

- Peripheral Blood Smear:Microscopic examination of blood cells can reveal the size and shape of red blood cells, confirming the macrocytic and hyperchromic morphology.

- Vitamin B12 and Folate Levels:Blood tests to measure levels of these vitamins.

- Bone Marrow Biopsy:In some cases, a bone marrow biopsy may be needed to evaluate the production of red blood cells.

Pathological Tests:

- Reticulocyte Count: Measures the rate of red blood cell production.

- Serum Bilirubin: Can be elevated in hemolytic anemia, which may be a related or differential diagnosis.

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH): May be elevated in hemolytic anemia.

- Indirect Coombs Test: Used to detect antibodies that may be causing red blood cell destruction.

- Hemoglobin Electrophoresis: May be necessary to rule out other hemoglobinopathies.

Treatment:

- Addressing the Underlying Cause: Treatment depends on the cause of the anemia.

- Vitamin B12 Supplementation: Injections or high-dose oral supplements are often used for B12 deficiency.

- Folate Supplementation: Oral folate supplements are used for folate deficiency.

- Blood Transfusions: In severe cases, blood transfusions may be necessary.

- Addressing Underlying Conditions: For example, treating celiac disease if it is causing malabsorption of B12 or folate.

Complications:

- Cardiovascular Problems: Severe anemia can lead to increased heart workload and potentially heart failure.

- Neurological Damage: Vitamin B12 deficiency can cause irreversible nerve damage if not treated.

- Increased risk of infections: Due to impaired immune function.

Prevention:

- Balanced Diet:Ensuring adequate intake of vitamin B12, folate, and other essential nutrients.

- Supplementation:Following recommendations for vitamin and mineral supplementation, especially during pregnancy.

Bleeding Disorders

Bleeding disorders are conditions where the blood doesn’t clot properly, leading to excessive or prolonged bleeding. Common types include Hemophilia (A and B), Von Willebrand disease, and various rare clotting factor deficiencies.

Common Bleeding Disorders:

- Hemophilia: A hereditary condition where the blood doesn’t clot properly due to a deficiency in clotting factors. Hemophilia A is a deficiency in factor VIII, and Hemophilia B is a deficiency in factor IX.

- Von Willebrand Disease (VWD): The most common inherited bleeding disorder, affecting the von Willebrand factor, a protein crucial for blood clotting and platelet adhesion.

Rare Bleeding Disorders:

- Factor XI (11) deficiency: Also known as Hemophilia C, characterized by a deficiency in clotting factor XI.

- Factor VII (7) deficiency: Deficiency in clotting factor VII.

- Factor X (10) deficiency: Deficiency in clotting factor X.

- Factor XIII (13) deficiency: Deficiency in clotting factor XIII.

- Hypofibrinogenaemia or dysfibrinogenaemia: Conditions affecting fibrinogen, a protein essential for clot formation.

- Prothrombin (factor II (2)) deficiency: Deficiency in clotting factor II.

- Factor V (5) deficiency: Deficiency in clotting factor V.

- Combined FV and FVIII deficiency: Deficiency in both factors V and VIII.

- Combined vitamin K dependent clotting factors deficiency (VKCFD): Deficiency in multiple vitamin K-dependent clotting factors.

Other Conditions:

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT): A rare inherited disorder that causes blood vessels to form abnormally, leading to bleeding.

Platelet disorders: Deficiencies or defects in platelets, which are blood cells crucial for clotting.

Thrombocytopenia: Low platelet count, leading to impaired blood clotting.

Thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome: A condition involving blood clots and low platelet count.

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS): A blood disorder that increases the risk of blood clots and pregnancy complications.

Anemia: A condition characterized by a low number of red blood cells, which can indirectly affect clotting.

Hemophilia

Hemophilia is a genetic bleeding disorder where the blood doesn’t clot properly due to deficiencies in clotting factors. It’s characterized by prolonged bleeding after injuries, easy bruising, and spontaneous bleeding. Diagnosis involves blood tests and specific factor assays. Treatment focuses on replacing the missing clotting factors, and complications can include joint damage and life-threatening bleeding. While not preventable due to its genetic nature, genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis can help families understand the risk.

Causes:

- Hemophilia is primarily caused by genetic mutations on the X chromosome, affecting the genes responsible for producing clotting factors VIII or IX.

- Hemophilia A: is caused by a deficiency in factor VIII, while Hemophilia B is caused by a deficiency in factor IX.

- Most cases are inherited, but about one-third of cases arise from spontaneous mutations.

- In rare instances, hemophilia can be acquired when the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own clotting factors.

Clinical Features:

- Prolonged bleeding: After injuries, surgeries, or dental procedures.

- Easy bruising: Especially deep bruises (hematomas).

- Spontaneous bleeding: Without a known cause, such as nosebleeds, bleeding into joints (hemarthrosis), or bleeding into muscles.

- Blood in urine or stool: Indicating internal bleeding.

- Joint pain and swelling: Due to bleeding into the joints.

- Irritability in infants: Due to potential internal bleeding.

- Bleeding gums: After tooth loss or dental work.

Diagnosis:

- Medical history and physical examination: To assess bleeding patterns and identify any potential risk factors.

- Blood tests:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To assess overall blood cell counts.

- Coagulation tests: Including activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and prothrombin time (PT) to assess clotting factors.

- Specific factor assays: To determine the level of specific clotting factors (VIII or IX).

- Genetic testing: To identify the specific gene mutation and confirm the diagnosis.

Pathological Tests:

- Prolonged aPTT: Indicates a problem with the intrinsic or common pathways of coagulation.

- Normal PT: Suggests that the extrinsic pathway of coagulation is intact.

- Low levels of factor VIII or IX: Confirms the specific type of hemophilia.

Treatment:

- Factor replacement therapy: Infusing the deficient clotting factor (VIII or IX) to temporarily correct the clotting defect.

- Prophylactic therapy: Regular infusions of clotting factors to prevent bleeding episodes.

- Desmopressin (DDAVP): A medication that can help release stored clotting factors, especially for mild hemophilia A.

- Antifibrinolytic medications: To help stabilize blood clots, particularly after dental work.

- Emicizumab: A newer medication that can be used for both hemophilia A and B.

Complications:

- Joint damage (hemophilic arthropathy): Repeated bleeding into joints can cause cartilage erosion and arthritis.

- Muscle and soft tissue bleeding: Can lead to pain, swelling, and limited mobility.

- Intracranial hemorrhage: Bleeding in the brain can be life-threatening.

- Infections: From blood transfusions or contaminated clotting factor concentrates.

Prevention:

- Hemophilia is a genetic condition, so it cannot be prevented.

- However, genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis can help families understand the risk of having a child with hemophilia and make informed decisions.

- For those with hemophilia, preventing complications through proper management and treatment is crucial.

Von Willebrand Disease (VWD)

Von Willebrand Disease (VWD) is a genetic bleeding disorder caused by a deficiency or defect in von Willebrand factor (VWF), a protein crucial for blood clotting. Symptoms include easy bruising, prolonged bleeding from cuts or after surgery, heavy menstrual periods, and nosebleeds. Diagnosis involves blood tests to assess VWF levels and function. Treatment options range from observation for mild cases to medications like desmopressin (DDAVP) or hormone therapy, and in severe cases, replacement therapy with VWF concentrates.

Causes:

- Inherited:VWD is primarily an inherited disorder, meaning it’s passed down from parents to children.

- Genetic Mutations:Mutations in the VWF gene lead to reduced or dysfunctional VWF.

- Autosomal Dominant/Recessive:Depending on the type of VWD, it can be inherited in an autosomal dominant (one copy of the mutated gene is enough) or autosomal recessive (two copies of the mutated gene are needed) manner.

- Acquired:In rare cases, VWD can be acquired due to other medical conditions like certain lymphomas or plasma cell disorders.

Clinical Features:

- Mucocutaneous Bleeding: This is the most common symptom, including frequent nosebleeds, easy bruising, and prolonged bleeding from minor cuts.

- Menorrhagia: Heavy menstrual bleeding is a significant symptom, especially in women.

- Bleeding After Procedures: Prolonged bleeding after dental work, surgery, or childbirth is also common.

- Gastrointestinal Bleeding: In severe cases, gastrointestinal bleeding can occur.

- Joint Bleeding: Bleeding into joints can occur in severe forms of the disease.

Diagnosis:

- Blood Tests:

- Von Willebrand factor antigen (VWF:Ag): Measures the amount of VWF protein in the blood.

- Von Willebrand factor activity (VWF:Act): Measures the ability of VWF to bind to platelets.

- Factor VIII activity: VWF and Factor VIII levels are often linked, so this test helps assess overall clotting ability.

- Multimeric analysis: Examines the structure of VWF molecules.

- Clinical History: A detailed bleeding history, including family history, is essential.

Pathological Tests:

- Blood tests: (as described above) are the primary pathological tests used to diagnose and classify VWD.

Treatment:

- Desmopressin (DDAVP):This synthetic hormone stimulates the release of VWF from the body’s storage and can be used for mild to moderate cases, before procedures, or to manage bleeding.

- Replacement Therapy:Concentrated VWF and Factor VIII concentrates are used for severe cases or when DDAVP is not effective.

- Oral Contraceptives:For women with heavy menstrual bleeding, oral contraceptives can help manage the bleeding.

- Anti-fibrinolytic Medications:Medications like tranexamic acid or aminocaproic acid can help stabilize blood clots and reduce bleeding, often used before or after procedures.

- Supportive Care:Wound care, pain management, and managing iron deficiency due to blood loss are also important.

Complications:

- Severe Bleeding: Can lead to anemia, requiring blood transfusions.

- Joint Damage: Recurrent bleeding into joints can cause long-term joint damage.

- Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Can be a serious complication, requiring medical intervention.

- Pregnancy and Childbirth: Women with VWD may experience complications related to bleeding during pregnancy and childbirth.

Prevention:

- Genetic Counseling:Couples with a family history of VWD should consider genetic counseling to understand the risk of passing the condition to their children.

- Awareness of Symptoms:Individuals with VWD should be aware of their condition and take precautions to avoid excessive bleeding.

Blood Clotting Disorders

Blood clotting disorders, also known as coagulation disorders, are conditions that affect the body’s ability to form blood clots properly. These disorders can lead to either excessive bleeding or excessive clotting, depending on the specific condition.

Types of Blood Clotting Disorders:

- Inherited:These disorders are passed down through families, such as Factor V Leiden, Prothrombin gene mutation, Protein C deficiency, Protein S deficiency, and Antithrombin deficiency.

- Acquired:These disorders develop during a person’s lifetime due to other illnesses, injuries, or medications. Examples include Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC).

Causes of Blood Clotting Disorders:

- Inherited:Genetic mutations affecting clotting factors or proteins involved in the clotting process.

- Acquired:Conditions like cancer, obesity, autoimmune disorders (like lupus), prolonged inactivity, and certain medications can increase the risk of blood clotting disorders.

Symptoms of Blood Clotting Disorders:

- Excessive Bleeding:Prolonged bleeding after injury or surgery, easy bruising, nosebleeds, heavy menstrual periods.

- Excessive Clotting:Deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism, strokes, and heart attacks.

Treatment of Blood Clotting Disorders:

- Medications:Anticoagulants (blood thinners) to prevent clots, or clotting factor replacement in cases of deficiencies.

- Other Treatments:Compression stockings, elevation of limbs, and other supportive measures to manage symptoms and prevent complications.

Specific Examples:

- Factor V Leiden:A common inherited disorder that increases the risk of DVT and pulmonary embolism.

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS):An autoimmune disorder that can cause blood clots in various parts of the body.

- Hemophilia:A group of inherited bleeding disorders caused by deficiencies in specific clotting factors.

- Von Willebrand Disease:The most common inherited bleeding disorder, where the blood doesn’t clot properly.

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC):A rare but serious condition where abnormal blood clots form throughout the body, potentially leading to both excessive bleeding and clotting.

Note: It’s crucial to consult with a healthcare professional for diagnosis and management of any suspected blood clotting disorder.

Blood Cancer

Blood cancers affect the bone marrow, lymph nodes, and lymphatic system, causing abnormal blood cells to grow uncontrollably. The main types are leukemia, lymphoma, and myeloma, but other forms include myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs). Common symptoms include unexplained bleeding, frequent infections, tiredness, and swelling.

Main Types of Blood Cancer

- Leukemia: is cancer of the white blood cells that starts in the bone marrow.

- Lymphoma: is cancer of the lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell) that starts in the lymphatic system, often forming tumors in lymph nodes.

- Myeloma: forms in the plasma cells in the bone marrow, which are a type of white blood cell that produces antibodies.

Other Types of Blood Cancer

- Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS): and Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPNs) are other categories of blood cancer affecting bone marrow function.

Common Symptoms

Symptoms vary by cancer type but can include:

- Easy bruising or bleeding

- Frequent or severe infections

- Unexplained fever or night sweats

- Persistent fatigue and weakness

- Bone pain or swelling in joints

- Unexplained weight loss

- Paleness or shortness of breath

- Swollen lymph nodes in the neck, underarms, or groin

What to Do if You Have Symptoms

If you experience any of these symptoms, it is important to consult with a doctor for proper diagnosis and treatment. Early diagnosis and treatment can significantly impact the outcome of the disease.

Leukemia

Leukemia is a cancer of the blood and bone marrow, characterized by the overproduction of abnormal white blood cells that impair the production of healthy blood cells. Causes include genetic mutations and potential environmental factors like chemical exposure, while common clinical features include fatigue, fever, unexplained bleeding or bruising, and swollen lymph nodes.

Definition of Leukemia

Leukemia is a cancer that starts in the blood-forming tissues of the bone marrow and the lymphatic system. It involves the excessive production of immature or abnormal white blood cells that are unable to function properly and crowd out healthy blood cells.

Causes of Leukemia

The exact causes are often unknown, but leukemia develops due to DNA mutations in hematopoietic stem cells. Risk factors and potential causes include:

- Genetic mutations: DNA changes in stem cells can cause them to multiply uncontrollably or resist normal cell death.

- Environmental factors: Exposure to certain chemicals (like industrial solvents or pesticides) and ionizing radiation can increase risk.

- Cancer treatments: Prior chemotherapy or radiation therapy for other cancers is a risk factor.

- Genetic conditions: Certain inherited conditions, such as Down syndrome, can increase the likelihood of developing leukemia.

- Smoking: Cigarette smoking is known to increase the risk of certain types of leukemia.

- Viral infections: Some viral infections may play a role in the development of leukemia.

Clinical Features of Leukemia

Symptoms can vary depending on the type of leukemia but may include:

- Fatigue and weakness: Anemia from reduced red blood cell production can cause these symptoms.

- Fever or chills: Due to the impaired ability of leukemia cells to fight infections.

- Unexplained bleeding or bruising: A lack of normal platelets can lead to easy bruising, bleeding gums, or recurrent nosebleeds.

- Petechiae: Tiny red spots on the skin caused by bleeding under the skin.

- Swollen lymph nodes: Lymph nodes may become enlarged.

- Bone pain or tenderness: Cancerous cells can accumulate in the bone marrow.

- Unintentional weight loss: Another potential symptom that can occur.

- Excessive sweating: Particularly at night.

- Frequent or severe infections: Due to the reduced number of functional white blood cells.

Investigation of Leukemia (Diagnosis)

- Initial Evaluation: A doctor will assess your symptoms (like fatigue, fever, bruising) and medical history.

- Blood Tests:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): This test reveals abnormal numbers of white blood cells, red blood cells, or platelets, which can indicate leukemia.

- Peripheral Blood Smear: Microscopic examination of blood cells helps identify cancerous cells.

- Bone Marrow Biopsy and Aspiration: This is a key diagnostic procedure where a small sample of bone marrow is removed from a large bone, like the hip, to be examined under a microscope.

- Genetic and Molecular Tests: These tests identify specific gene mutations or chromosome changes in the leukemia cells, which helps to determine the specific type and subtype of leukemia and its prognosis.

- Imaging Tests: X-rays, CT scans, MRIs, or bone scans may be used to look for infections or other issues related to leukemia, though they are not primary diagnostic tools for leukemia itself.

- Lumbar Puncture (Spinal Tap): A needle is used to collect cerebrospinal fluid to check if the leukemia has spread to the brain or spinal cord.

Treatment of Leukemia

Treatment is highly dependent on the type and stage of leukemia, as well as the patient’s overall health and age.

- Chemotherapy: Uses drugs to target and kill fast-dividing cells, often used for acute leukemia.

- Targeted Therapy: Uses medicines that attack specific molecules or proteins in cancer cells, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) for chronic myelogenous leukemia.

- Immunotherapy: Harnesses the patient’s own immune system to fight the cancer. CAR-T cell therapy is a type where a patient’s T cells are engineered to fight leukemia cells.

- Radiation Therapy: May be used to kill cancer cells or prevent their spread to other areas.

- Stem Cell Transplantation (Bone Marrow Transplant): Replaces the patient’s damaged bone marrow with healthy stem cells to produce new, healthy blood cells.

- Clinical Trials: Offer access to experimental treatments and therapies that are not yet widely available.

- Watchful Waiting: For some types of slow-dividing chronic leukemia, doctors may monitor the disease without immediate treatment.

Complications of Leukemia

Leukemia complications arise from the overproduction of abnormal white blood cells, which crowd out normal cells in the bone marrow, and from treatment side effects.

- Infections: A lack of healthy white blood cells makes it harder for the body to fight off infections.

- Bleeding: Low platelet counts can lead to easy bruising and bleeding, including nosebleeds, bleeding gums, or petechiae (tiny red spots on the skin).

- Anemia: A shortage of red blood cells causes fatigue, weakness, and shortness of breath.

- Weight Loss: Unexplained weight loss can be a symptom or a side effect of leukemia and its treatments.

- Tumor Lysis Syndrome: This is a dangerous condition caused by the rapid breakdown of cancer cells, which can lead to kidney damage and other problems.

- Other Complications: In children treated for acute leukemia, late effects can include slowed growth, infertility, or even an increased risk of other cancers.

Preventing Leukemia

There is no guaranteed way to prevent leukemia, as the exact causes are not fully understood. However, you can lower your overall risk by taking steps to avoid known risk factors:

- Avoid Tobacco: Don’t use tobacco products in any form, and avoid secondhand smoke.

- Limit Chemical Exposure: Reduce your exposure to substances like benzene (found in gasoline and cigarette smoke) and certain pesticides.

- Limit Radiation Exposure: Avoid unnecessary exposure to high-dose ionizing radiation.

- Adopt a Healthy Lifestyle: Maintain a healthy body weight, get regular physical activity, and eat a diet rich in fruits and vegetables.

- Be Mindful of Previous Treatments: Be aware that prior chemotherapy or radiation therapy can increase leukemia risk later in life.

Lymphoma

Lymphoma is a blood cancer of the immune system’s lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell) that grow out of control, forming masses of abnormal cells. Causes are often unknown but can involve immunodeficiency, autoimmune diseases, infections like Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), exposure to certain chemicals and radiation, and genetic factors. Clinical features frequently include painless lumps (especially in the neck, armpit, or groin), unexplained weight loss, persistent fever, and drenching night sweats.

Definition

- Lymphoma is a cancer of the lymphatic system, which is part of the immune system.

- It starts when white blood cells called lymphocytes become abnormal and multiply uncontrollably.

- There are two main types: Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which differ in the type of lymphocyte affected.

Causes

- In most cases, the specific cause of lymphoma is unknown.

- Immunodeficiency: A weakened immune system from conditions like HIV or organ transplants increases the risk.

- Infections: Certain infections are linked to an increased risk, including Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), hepatitis C, and the Helicobacter pylori bacteria in some stomach lymphomas.

- Environmental Factors: Exposure to certain chemicals in pesticides, fertilizers, and herbicides, as well as nuclear radiation, are associated with higher risk.

- Autoimmune Diseases: Conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, celiac disease, and lupus can raise the risk.

- Age: While it can affect any age group, it is more common in older adults.

Clinical Features

- Swollen Lymph Nodes: The most common symptom is a painless lump or lumps, typically in the neck, armpit, or groin, that lasts for more than a couple of weeks.

- Fever: A persistent fever without a known infection.

- Night Sweats: Drenching night sweats.

- Weight Loss: Unexplained, unintentional weight loss.

- Fatigue: Extreme tiredness or a lack of energy.

- Itching: Unusual itching of the skin.

- Abdominal Symptoms: Discomfort or feeling uncomfortably full in the stomach area.

- Cough and Breathlessness: Chest pain, coughing, and shortness of breath.

Diagnosis

- Medical History and Physical Exam: The process begins with a doctor assessing your symptoms and performing a physical exam to check for swollen glands or masses.

- Biopsy: A tissue sample is removed from a suspicious lymph node or mass and examined under a microscope by a pathologist to confirm the presence of lymphoma cells.

- Bone Marrow Biopsy: A sample of bone marrow is taken to see if the lymphoma has spread to the bone.

- Blood Tests: Tests like a complete blood count (CBC), liver and kidney function tests, and tests for inflammation (like ESR) are performed to assess overall health and check for signs of lymphoma affecting other organs.

Investigation (Staging)

After a diagnosis, further tests are done to determine the extent (stage) of the lymphoma:

- Imaging Tests:

- CT (Computed Tomography) Scan: Used to visualize enlarged lymph nodes and organs like the spleen and lungs.

- PET (Positron Emission Tomography) Scan: Can show areas of high metabolic activity, indicating cancer cells, which helps determine distant spread, according to Cancer Australia.

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) Scan: May be used in addition to CT scans for detailed imaging.

- Lumbar Puncture: A spinal tap may be performed to collect cerebrospinal fluid and check for lymphoma cells in the central nervous system, particularly if neurological symptoms are present.

Treatment

Treatment options depend on the type and stage of the lymphoma, as well as the patient’s overall health:

- Chemotherapy: Uses drugs to kill cancer cells.

- Radiation Therapy: Uses high-energy rays to destroy lymphoma cells.

- Immunotherapy:

- Monoclonal Antibodies: Laboratory-made proteins that target specific markers on lymphoma cells to help the immune system destroy them.

- CAR T-cell Therapy: T-cells are removed, engineered in a lab to recognize and attack lymphoma cells, and then infused back into the patient.

- Stem Cell Transplant: May be used for relapsed or aggressive lymphomas, often involving high-dose chemotherapy to prepare the body for new stem cells.

Complications of Lymphoma

- Increased Risk of Infections: Lymphoma and its treatments can weaken the immune system, making individuals more vulnerable to bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.

- Secondary Cancers: Treatments like chemotherapy and radiotherapy can increase the risk of developing other cancers, such as breast, lung, or leukemia, years later.

- Organ Damage: Chemotherapy and radiation can cause long-term damage to organs such as the heart and lungs, as well as damage to nerves, leading to symptoms like pain, numbness, or tingling.

- Fertility Problems: Some cancer treatments can affect a person’s fertility, leading to temporary or permanent infertility.

Prevention of Lymphoma

- Healthy Lifestyle:

- Diet: Eat a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, while limiting processed meats and sugary drinks.

- Exercise: Regular physical activity helps maintain a healthy weight and supports a strong immune system.

- Weight: Maintaining a healthy weight can reduce the risk of several cancers, including lymphoma.

- Avoid Tobacco: Quitting smoking is crucial, as it increases the risk of various cancers.

- Manage Infections: Protect yourself from infections linked to lymphoma, such as HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

- Reduce Exposure: Limit exposure to harmful substances like certain pesticides and radiation by following safety guidelines.

- Regular Check-ups: Early detection through regular check-ups can improve the effectiveness of lymphoma treatment.

Myeloma

Myeloma is a type of bone marrow cancer caused by abnormal plasma cells that produce harmful, non-functional antibodies called paraproteins. Symptoms include Calcium elevation (hypercalcemia), Renal (kidney) damage, Anemia (low red blood cells), and Bone pain, often accompanied by fatigue and infections. While the exact cause is unknown, myeloma develops from DNA mutations in developing plasma cells, with potential risk factors including exposure to certain chemicals and radiation.

Definition

- Myeloma, also known as Multiple Myeloma, is a cancer of plasma cells, a type of white blood cell found in the bone marrow.

- Normal plasma cells produce antibodies to fight infection, but in myeloma, these cells become cancerous, multiplying and producing a single type of abnormal antibody (paraprotein) that doesn’t help the body fight infection.

- These abnormal plasma cells and paraproteins can build up in the bone marrow, blood, and urine, crowding out healthy blood cells and causing damage to organs.

Causes

- Myeloma starts when a developing plasma cell undergoes a gene mutation, transforming it into a cancerous myeloma cell.

- This mutation is not typically inherited but occurs during a person’s lifetime.

- While the specific trigger for these mutations isn’t always known, potential risk factors may include exposure to certain industrial and agricultural chemicals and high doses of radiation.

Clinical Features

Clinical features are often remembered by the acronym CRAB:

- C alcium elevation (Hypercalcemia): High levels of calcium in the blood, released from damaged bones.

- R enal failure (Kidney damage): The paraprotein can damage the kidneys, leading to dysfunction.

- A nemia: The bone marrow’s inability to produce healthy red blood cells results in low red blood cell counts.

- B one pain and lytic lesions: Cancerous plasma cells can destroy bone tissue, causing pain, weakness, and a high risk of fractures.

Other common symptoms include: Fatigue and weakness, Increased susceptibility to infections, Unexplained weight loss, and Numbness or tingling in the limbs.

Diagnosis and Investigation

- Blood Tests:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Checks for low levels of red blood cells (anemia), white blood cells, and platelets.

- Blood Chemistry: Measures levels of creatinine (for kidney function), calcium, and other proteins like albumin and beta-2-microglobulin.

- M Protein/Immunoglobulin Tests: Checks for high levels of M protein (a sign of myeloma) and abnormal immunoglobulin (antibody) levels in the blood.

- Serum Free Light Chain Assay: Specifically measures kappa and lambda light chains in the blood, which is a sensitive marker for myeloma.

- Urine Tests:

- 24-Hour Urine Collection: Measures Bence Jones protein (another type of M protein) in the urine.

- Bone Marrow Tests:

- Aspiration and Biopsy: A sample of bone marrow is removed to confirm the presence of malignant plasma cells and assess their percentage.

- Cytogenetic Testing: Genetic tests (like FISH and karyotyping) performed on bone marrow cells help determine the disease’s aggressiveness and risk.

- Imaging Tests:

- Skeletal Survey/X-rays: Identifies lytic lesions (holes) or weakened areas in the bones caused by myeloma.

- MRI/CT Scans: Provide detailed pictures of the body to find any bone damage or involvement of other organs.

Treatment

Treatment depends on factors like age, overall health, and the disease’s stage.

- Systemic Treatment:

- Chemotherapy: Drugs that kill cancer cells.

- Targeted Therapy: Medications that target specific proteins or pathways in cancer cells, such as proteasome inhibitors (e.g., bortezomib).

- Immunotherapy: Treatments that use the immune system to fight cancer, including monoclonal antibodies (e.g., daratumumab).

- Corticosteroids: Steroid medications that are often used in combination with other treatments.

- Stem Cell Transplantation:

- Autologous Stem Cell Transplant: High-dose chemotherapy is followed by the infusion of the patient’s own collected stem cells.

- Supportive Care:

- Bone Health: Bisphosphonate therapy is used to prevent bone loss and strengthen bones.

- Infection Prevention: Prophylactic measures to protect against infections.

- Pain Management: Medicines and other treatments for bone pain.

Complications of Myeloma

Myeloma, a cancer of plasma cells, can lead to various complications because of abnormal M-protein production.

- Bone Complications: Overproduction of M-proteins can lead to weakened bones, causing pain, holes in bones, and an increased risk of fractures and spinal cord compression. High calcium levels in the blood (hypercalcemia) are also a consequence.

- Kidney Damage: The paraprotein can damage the kidneys, leading to renal insufficiency. Dehydration, hypercalcemia, and infections can also contribute to kidney problems.

- Infections: Myeloma patients are at a higher risk for infections, particularly pneumonia and pyelonephritis, due to a weakened immune system.

- Hematologic Complications: Anemia (low red blood cell count) and bleeding disorders are common.

- Neurologic Complications: Nerve compression from bone lesions can cause neurological issues.

- Other Complications: Symptoms like confusion, increased thirst, fatigue, and weight loss can also occur.

Prevention of Complications

Preventing or managing these complications involves proactive management of the disease and its treatment.

- Hydration: Drink plenty of fluids, like water, to help flush toxins and maintain blood volume and pressure, which can protect the kidneys.

- Regular Monitoring: Get regular check-ups to monitor kidney function (e.g., creatinine levels) and bone health.

- Infection Management: Promptly report any signs of infection to your doctor, as they can be serious.

- Lifestyle Adjustments: Stay active and talk to your doctor about whether you need to take blood thinners to prevent blood clots, which can be a side effect of some treatments.

- Medication Awareness: Be aware that certain medications, including some treatments for myeloma, can cause side effects like neuropathy or hormone imbalances.

- Emotional Support: Seek support for anxiety, depression, and other emotional challenges that can arise from a cancer diagnosis.

Thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia is a medical condition defined by a low platelet count in the blood, leading to easy bleeding and bruising. Causes include decreased platelet production (due to bone marrow issues or infections), increased platelet destruction (from autoimmune diseases or certain medications), and splenic sequestration. Clinical features manifest as symptoms of poor clotting, such as prolonged bleeding from minor injuries, nosebleeds, bleeding gums, blood in the urine or stool, easy bruising, and petechiae (tiny red spots on the skin).

Definition

- Low platelet count: Thrombocytopenia is a condition characterized by having fewer than the normal number of platelets (thrombocytes) in your blood.

- Platelet function: Platelets are essential blood cells that form plugs to stop bleeding and activate clotting factors when you have an injury or cut.

- Normal range: For adults, a normal platelet count typically ranges from 150,000 to 450,000 platelets per microliter of blood.

Causes

Thrombocytopenia can arise from three main mechanisms:

- Decreased Production: The bone marrow, which produces platelets, doesn’t make enough.

- Examples: Bone marrow disorders (like aplastic anemia), certain cancers (leukemia, lymphoma), severe infections, and nutrient deficiencies (B12, folate).

- Increased Destruction or Utilization: More platelets are destroyed or used up than the body can replace.

- Examples: Immune system disorders (like lupus), viral infections, certain medications (some antibiotics, heparin), and conditions like thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP).

- Splenic Sequestration: The spleen, which stores platelets, becomes enlarged, trapping a larger number of platelets.

- Examples: Liver disease can lead to an enlarged spleen, causing more platelets to accumulate in the organ.

Clinical Features

Symptoms arise from the body’s inability to form blood clots effectively:

- Easy Bruising: You may notice bruises appearing more easily and lasting longer than usual.

- Bleeding:

- Prolonged Bleeding: Cuts may take a long time to stop bleeding.

- Mucocutaneous Bleeding: You might experience nosebleeds, bleeding from your gums, or heavy menstrual bleeding.

- Blood in Waste: Blood may be seen in your urine or stool.

- Skin Changes: Pinpoint red spots on the skin, called petechiae, can be a sign of excessive bleeding under the skin.

- Internal Bleeding: In severe cases, especially with very low platelet counts, spontaneous internal bleeding can occur.

Diagnosis of Thrombocytopenia

- History and Physical Exam: A doctor will ask about symptoms like easy bruising or bleeding, and perform a physical exam to look for signs of bleeding.

- Blood Tests:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Measures platelet levels and other blood cells to confirm the low platelet count.

- Blood Smear: A sample of blood is examined under a microscope to check the shape and appearance of platelets and other blood cells.

- Further Investigations: Based on the initial findings, further tests are done to find the cause:

- Bone Marrow Aspiration and Biopsy: To evaluate the bone marrow’s health and ability to produce platelets.

- Imaging Tests: Such as an ultrasound, CT, or MRI to check for an enlarged spleen or liver abnormalities.

- Other Blood Tests: To look for infections (e.g., HIV, Hepatitis), autoimmune markers (e.g., antiphospholipid antibodies), or signs of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

Investigation of Thrombocytopenia

Investigations are guided by the clinical history and physical exam, with tests aimed at identifying the underlying cause.

- Urgent Investigations: Required for red flag signs such as a very low platelet count (below 10 x 10³ per μL), significant bleeding, or the presence of other serious conditions like thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) or DIC.

- Infection Screening: Blood tests for viral infections like HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and cytomegalovirus.

- Autoimmune Markers: Blood tests for antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) or antiphospholipid antibodies if an autoimmune cause is suspected.

- Coagulation Tests: Prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) tests to assess blood clotting if a bleeding disorder is suspected.

Treatment of Thrombocytopenia

Treatment depends on the cause, severity, and presence of symptoms.

- Treat the Underlying Cause:

- Medication-induced: Discontinuing the causative drug, such as heparin for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

- Infection-related: Treating the underlying infection.

- Medications:

- Corticosteroids: To suppress the immune system in immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

- Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG): Another immune-suppressing therapy for ITP.

- Thrombopoietin Receptor Agonists: Medications that stimulate platelet production.

- Procedures:

- Platelet Transfusions: For severe bleeding, to temporarily increase platelet levels.

- Plasma Exchange: Used for some severe clotting disorders to remove harmful components from the plasma.

- Splenectomy: Surgical removal of the spleen, which can be beneficial if the spleen is enlarged and other treatments have not worked.

Complications

- Bleeding: The most common complication is an increased risk of bleeding due to impaired blood clotting.

- Internal bleeding: This can occur into the brain (causing neurological symptoms) or the intestines, which is a serious and potentially fatal complication.

- Other signs: Easy bruising (purpura), pinpoint red dots on the skin (petechiae), prolonged bleeding from minor cuts, nosebleeds, gum bleeding, and heavy menstrual flows can also occur.

- Thrombosis (Blood Clots): While less common, some conditions associated with low platelets can also lead to blood clot formation.

- Conditions: These include heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS), thrombotic microangiopathies (like TTP or HUS), and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

Prevention of Complications

- Avoid injury: Limit or avoid activities that carry a high risk of bruising or bleeding, such as contact sports.

- Medication caution:

- Avoid aspirin and ibuprofen: These over-the-counter medicines can interfere with platelet function and thin the blood too much.

- Inform providers: Always tell your healthcare provider about any medications you are taking, especially before surgery or dental procedures.

- Lifestyle choices:

- Limit alcohol: Heavy alcohol use can affect platelet levels and production.

- Quit smoking: Smoking increases the risk of blood clots.

- Practice good hygiene: Maintain good dental hygiene to avoid bleeding from the gums.

- Vaccination: Discuss relevant vaccinations, such as for measles, mumps, rubella, and chickenpox, with your healthcare provider, as some viral infections can affect platelet counts.

Prevention of Thrombocytopenia

- Preventing thrombocytopenia depends on its cause, and it cannot always be prevented.

- Address underlying conditions: Managing chronic conditions that may lead to low platelets, such as certain autoimmune diseases or infections, can help.

- Avoid toxins: Limit exposure to toxic chemicals like pesticides and benzene, which can slow platelet production.

Sickle Cell Disease

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of inherited red blood cell disorders where the red blood cells become rigid, C-shaped (sickle-shaped), and die early, leading to anemia and blocked blood flow that causes pain and serious organ damage. SCD is caused by inheriting an abnormal hemoglobin gene from both parents. Clinical features include chronic hemolytic anemia (leading to jaundice, weakness), vaso-occlusive crises (pain crises), increased risk of infection due to spleen damage, stroke, acute chest syndrome, kidney problems, and organ damage.

Definition of Sickle Cell Disease

- Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of inherited red blood cell disorders.

- It causes the body’s hemoglobin (the protein that carries oxygen) to be abnormal, leading to sickle-shaped red blood cells.

- These sickle cells are rigid and sticky, blocking blood flow in small blood vessels and dying earlier than normal red blood cells.

- This results in a constant shortage of red blood cells and organs not getting enough oxygen.

Causes of Sickle Cell Disease

- SCD is a genetic, or inherited, disorder, meaning it is passed down from a parent’s genes.

- A child is born with SCD only if they inherit one sickle cell gene from each parent.

- This usually happens when both parents are “carriers” of the gene, meaning they have the sickle cell trait but do not have the disease themselves.

Clinical Features of Sickle Cell Disease

- Anemia: The sickle cells die early, causing a chronic shortage of red blood cells, which can lead to symptoms like fatigue, weakness, and jaundice.

- Vaso-occlusive Crises (Pain Crises): Sickle cells can get stuck in blood vessels, blocking blood flow and causing sudden, severe pain. These pain episodes can affect any part of the body, but often occur in the chest, back, limbs, and abdomen.

- Increased Infections: Sickle cells can damage the spleen, which helps filter out bacteria. A damaged spleen makes individuals with SCD more susceptible to serious infections, especially in childhood.

- Stroke: Blocked blood flow can also affect the brain, leading to strokes and other neurological issues.

- Acute Chest Syndrome: Blockages in the lungs can cause acute chest syndrome, a serious condition that lowers oxygen levels in the blood.

- Organ Damage: Over time, the blocked blood flow can damage various organs, including the heart, kidneys, and liver.

- Swelling: Pain and swelling in the hands and feet, known as dactylitis, is often an early sign of SCD in young children.

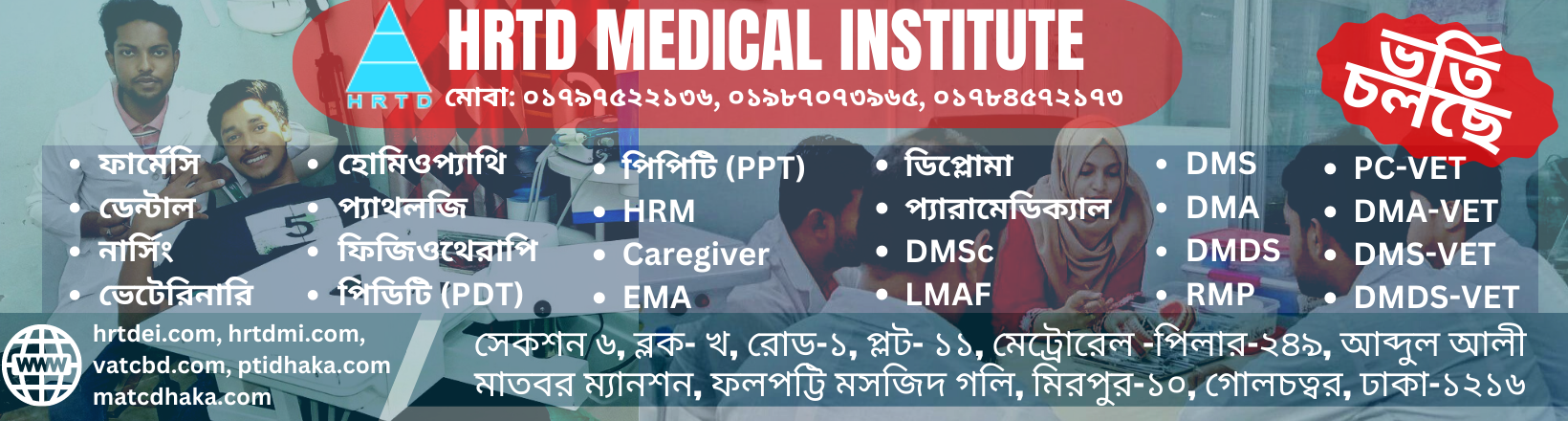

HRTD Medical Institute

HRTD Medical Institute